I want to tell you a story that happened many years ago, as recently as today, and will happen again tomorrow. It is a story about a deceptively familiar place where securing the basic necessities of life, health care, housing, transportation, and communication requires persistence to overcome one obstacle after another.

Our story begins on a bright September morning when I agreed to take Trila to her scheduled hearing aid appointment. I drove thirty miles to the audiologist’s office, and while Trila wandered down the hall to the restroom, I told the nurse the reason we were there. She disappeared, returned, and, sliding the glass panel back open, said gently, “I’m sorry, but her Medicaid supplement won’t reimburse us so we cannot examine her.” The only solution to ease Trila’s disappointment was to make the 198-mile round trip to the closest audiologist who would accept Trila’s Medicaid supplement. Three visits later, Trila sat in the passenger seat clutching the sturdy little storage case meant to keep her brand new hearing aids safe and sound.

“Now,” she said beaming from ear to ear, “you don’t have to yell no more, cause I can hear you!”

The moment I accepted that a 198-mile trip was the only way around the insurance obstacle, I stepped into the parallel universe inhabited by hundreds of thousands of Americans.

Universal Declaration of Human Rights, Article 25: Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and well-being of him/herself and of their family including food, clothing, housing and medical care and necessary social services, and the right to security in the event of unemployment, sickness, disability, widowhood, old age or other lack of livelihood in circumstances beyond their control.

Trila is a woman in her mid-fifties and extremely hard of hearing who ended up on the street when the city condemned the house in which she was living. Painful injuries from a near-fatal childhood car accident continue to worsen as she ages. She is a survivor of abuse, and the mother of three children. She likes to read and do jigsaw puzzles. She loves a hot cup of coffee with cream, a peppermint Frosty, horses, and fishing. Her companions for the past few years have been a fluid community of street people sharing cigarettes, food, memories, and dreams. This is her/their story of transition.

After patiently waiting more than a year, Trila was assigned an apartment in a mixed-income neighborhood on the outskirts of a town of 14,000 people, twenty-three miles away from me and life on the streets. She was given a bed along with several pieces of furniture, a tub mat, shower curtain, and a few pots and pans.

It wasn’t long before Trila started dreaming of a vegetable garden along the back fence. With Christmas just around the corner, she sent greeting cards with a return address of her very own.

January 2 brought devasting news: the debit card Trila had used every month for the past ten years was denied access to her Social Security payments account. She faced the New Year with seven one-dollar bills and sixteen pennies in her pocket. It took two months of phone calls, with a dizzying array of reasons given for the screwup, before her SSI payments showed up in her bank account. In the meantime, electric service was cut off, a $45 late fee was added to her unpaid water bill, and a letter arrived from the landlord demanding immediate payment.

Without any financial resources of her own, Trila faced eviction solely because a financial institution 245 miles away decided to close her debit account. Fortunately, a no-interest loan from a friend enabled her to stay in the place she had begun to call home, with its view of horses in the pasture out the kitchen window.

Early in Trila’s transition from street to apartment I realized that without reliable transportation, many of her practical and emotional needs could not be met, so our get-together Wednesdays were born. On this particular Wednesday, Trila rode back to Wilmington with me, ostensibly to locate her older brother, whose last known address was in a low-income apartment unit on the south end of town. The sign on the office door read CLOSED in large red letters; OPEN: Thursday and Saturday 9-noon.

She walked slowly back to the car, slumped against the seat, and stared out the front window. Her head gave that abrupt nod that I have come to know indicates she’s made up her mind about something. “Can we go to the cemetery?”

I nodded and started the car. We rode in silence across town and through the front gate.

“I want the baby cemetery.” She pointed. “Up there on the hill.” Trila retrieved the bouquet of plastic flowers from between her feet, gently closed the passenger door, and said, “Come and see.”

We stopped beside a small brown gravestone. Trila bent over, swept away the tree debris with her right hand, and sat down. She lovingly laid the flowers on top of her son’s stone: Baby Harley. He never saw his second birthday.

Though I have no graves to visit, I, too, need space to grieve the death of members of my family and wonder about the what-ifs. “Take as much time as you need,” I said. “I’ll wait in the car.”

Query: Do we acknowledge the oneness of humanity and foster a loving spirit toward all people? [New York Yearly Meeting]

Trila must get a ride to the bank when her Social Security (SSI) payment goes into her account on the first of each month. With cash in her fanny pack, she makes the rounds to pay her rent (at a second bank), electric bill (Kroger service desk), and water bill (downtown office). When the Food Stamps arrive, Trila needs a ride to the grocery store, buys only what is covered by Food Stamps, and does not exceed her Food Stamp allotment. Once a month, a third ride takes her to the Free Store for toilet paper and paper towels — if the Free Store has any left on the shelf. A fourth taxicab takes her to the Dollar Store for shampoo and dog food, dish and laundry detergent, and a fifth to Second Chance or Goodwill for other non-food items. These five round trips require ten pickups at $7.00 apiece for a total of seventy dollars.

I drive to Kroger several times a week, use a credit card to buy whatever food I’m in the mood for, toss a package of toilet paper, my favorite shampoo and matching conditioner, along with dog food and a new floor mop, into the cargo space in my little SUV. Easy-peasy one-stop-shopping. I might even swing through McDonald’s on my way home. And of course, I could pay my utility bills online.

When there is “too much month left at the end of the money,” Trila’s meals consist of bread with peanut butter, a can of creamed corn or beans, and a cup of instant coffee.

I have never spent two weeks eating the remnants in my cupboard.

Query: Am I careful to avoid judging others based on their social position, intellectual ability or economic condition? [Wilmington Yearly Meeting]

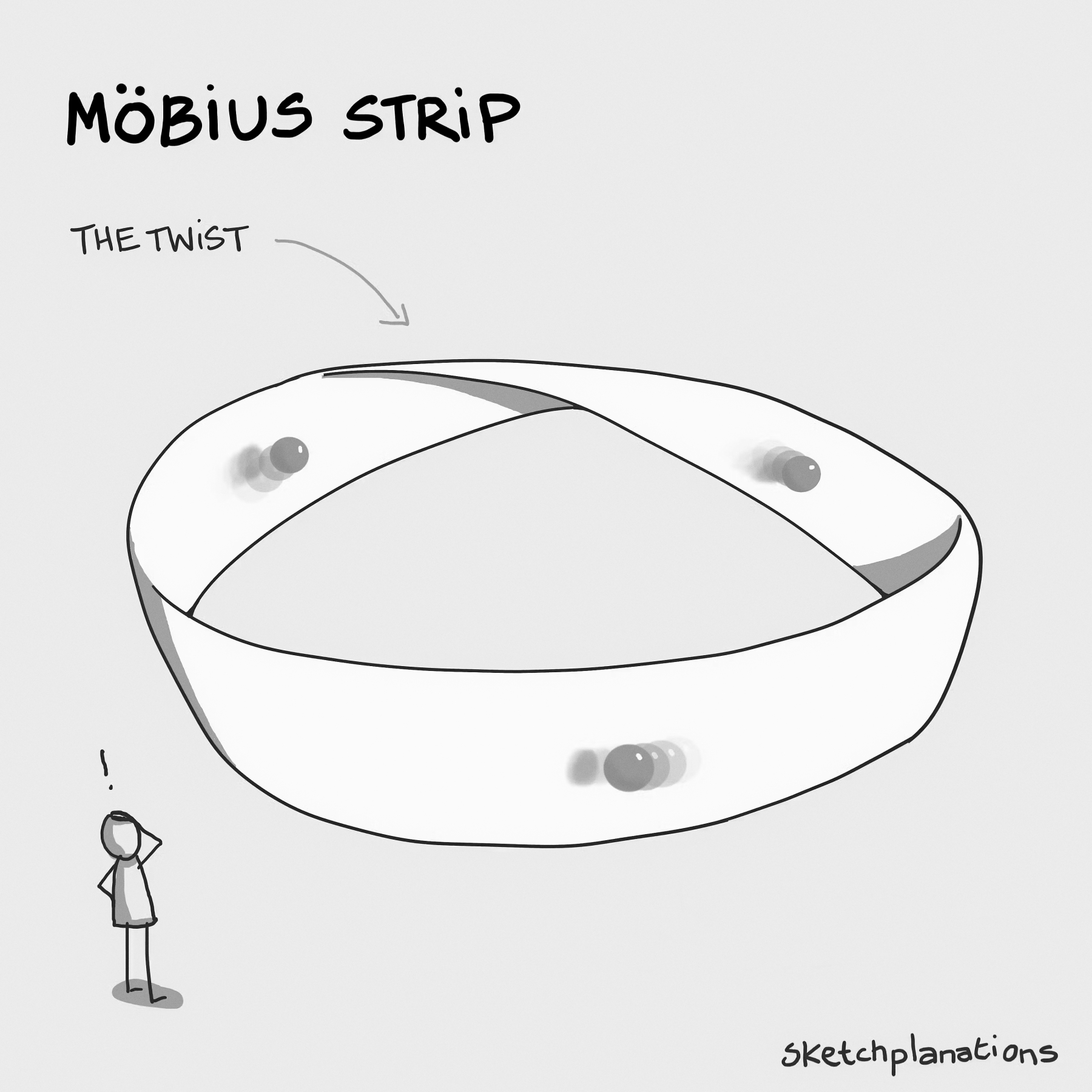

The transition into a place of her own feels like trying to navigate a mobius strip. Complete the first loop and you find yourself upside down and only half-way to your destination. Complete the second loop and you are back to where you started, feeling a bit dizzy and discombobulated by the experience. Come and see.

After years of medical care consisting of trips to Urgent Care and the ER, Trila totally gets the importance of coordinated personal health care, but the reality is Trila is dependent on public transportation, which does not exist in her mid-sized town. Job and Family Services (JFS) offers free transportation to and from medical appointments for Trila as a qualified Medicaid recipient — IF she calls them once a month and leaves her name, social security number, address, and birthdate; IF she requests transportation at least fortyeight hours before the appointment; IF there are sufficient drivers; and, IF enough places are still available in the van. When the van does not show up, Trila must make some phone calls.

However, because she is extremely hard of hearing, making phone calls is a daunting experience. The first obstacle is the selection of options from a confusing menu. When people talk very fast, or English is their second language, even hearing aids do not make it possible to understand instructions.

“Call a cab,” suggests her attempting-to-be-helpful nextdoor neighbor. “It’s seven dollars each way, but I think JFS has vouchers you can use.”

“Yes, we have reimbursement vouchers. Just pay your cab fare, bring the driver and health provider signed voucher to our office, and we will reimburse you by check once a month.”

“I don’t have $14 for cab fare.”

“That’s okay. JFS can reimburse the taxi driver directly. Just come by our office and pick up some vouchers for the driver to sign.”

“I live five miles away. How am I going to get to your office?” Close to tears, Trila listens into the silence coming from the other end and hangs up.

Forty-five minutes later my phone rang. “Trila did not show up for her doctor’s appointment today,” the recorded voice informs me. “Please call to make another appointment.”

In fairness to the overworked folks at Job and Family Services, their office is so understaffed they no longer answer the phone. Using a triage system, they work their way through the messages one by one, returning the most urgent ones first — a creative response to a difficult situation. But the bottom line remains: if I cannot make the trip, then neither can Trila.

The health care system Trila uses is excellent. However, the orthopedics and pain management specialists are fortytwo miles away, and you must have a car to get there. In mid-July another obstacle popped up: to keep her Medicaid, Trila must now keep a list of all medical trips in a private car to, one, prove she kept the appointment, and, two, to enable reimbursement to the driver for gas. We are averaging four medical trips a month. That’s a lot of bookkeeping.

Query: Do I treat others the way I want to be treated? [ “Queries for Children,” Wilmington Yearly Meeting]

In order of difficulty, the conundrum presented by inaccessible internet is a close second to unreliable transportation. Consider the number of times you are instructed, “Go to our website for further information;” “Create a medical portal to track your results and contact your provider;” “Our free fair for babies’ needs is this Saturday register on our website.” Functioning successfully in today’s connected world requires access to a computer and the internet.

But life on the street does not provide the knowledge and experience needed to negotiate the world wide web especially when the library staff is not amenable to your presence. In the parallel universe every transaction must be accomplished by snail mail, cell phone, or in person.

Thus, the death of a cell phone is disastrous. A replacement runs from seventy to over a thousand dollars. It is almost impossible to apply for a job, leave a call-back number, ask for an appointment, or arrange transportation. Because the only way to communicate is meeting in person, Trila is for all intents and purposes cut off from the community.

Commitment to equality has an impressive history in this country: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal . . . endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable rights . . . among them are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of happiness.” The Universal Declaration of Human Rights begins, “All human beings are born free and equal in dignity and rights. These are not a reward for good behavior . . . they are the inalienable entitlements of all people at all times and in all places.”

Experience leads me to believe the Trilas in our communities are doing all they can to maintain a home of their own and get back on their feet, but because something happened between “as you do unto the least of these my brothers and sisters, that you do unto me,” (Matt. 25:40) and, “the homeless are not welcome in this town,” they may spend the rest of their lives in the parallel universe trying to navigate the Mobius strip.

And yet I wonder, if thousands of us help make even one or two steps less formidable in the transition from street to a place of one’s own, might we creep toward a time when it is no longer true that “Equality is just people talking?”

I Won’t be Equal Until my People are Equal, Karla Jay

Quaker Exceptionalism, Max Carter

Equality, Charity Kemper Sandstrom

To Serve Beside My Brothers, Charity Kemper Sandstrom

No Risk Factors, Gabrielle Savory Bailey

La equidad no pudo venir/ Equity could not come, Jorge Luis Peña, translated by Ben Snyder

When Equal is not Fair, Craig Strafford

Article 25, Patricia Thomas

Bible Study: Spiritual Equality and Meeting Life, Kelly Kellum

The Luminous Darkness, Howard Thurman

It surprised me how difficult it was to find contributors on this theme. It has taken nearly eighteen months to gather these articles; some of those we invited to contribute declined, while others who accepted wrote slowly. I don’t believe that people were unmoved by the topic; I suspect, rather, that our collective hesitation to write about equality is an embarrassed recognition that Quakers have not been as “exceptional” (to use the word Max Carter uses) in our enactment of equality as other groups believe we have been — and, based on our early theology, as we expect ourselves to have been.

Be that as it may, equality or the lack thereof is herein considered in a wide array of appearances: from homelessness and impoverishment to the pulpit, American Indians to emergency rooms, segregation to immigrant communities to the Cuban state.

Patricia Thomas writes about how the homeless, or recently re-homed, who are cut off from transportation and computers, live in a parallel universe in which the basic goods and services which sustain modern life — like banking and bill-paying, for example — are far more difficult to access for those with the least resources than they are for those who have less need. Informed by his own work with the impoverished, Craig Strafford explains the differences between equality and equity, particularly when measured by outcomes.

Karla Jay writes about her feeling of responsibility, as a naturalized citizen raised in the Unites States, for the members of her immigrant community who were not raised here, and who don’t know how to navigate the legal and economic structures of life in Indiana. She is willing to bear this responsibility, she writes, because earlier immigrants bore it for her.

In an excerpt from his book, The Luminous Darkness, Howard Thurman considers the effect on children, both white and black, of being raised to believe that some people exist so clearly outside the sphere of personhood that behavior toward them doesn’t belong to the realm of morality, of ethics. There is as little consideration of good or bad in one’s behavior toward this category of person (which might be White, Black, German, Japanese, or any other nationality or race which has been placed beyond this boundary) as there is toward a table or chair.

In two essays, pastor Charity Kemper Sandstrom writes about her experience as a woman pastor among Friends who affirm by written statements the equality of women as leaders but fall woefully short of that standard in practice.

Max Carter writes about the idea that Friends, an exception to the rule, recognized the American Indians as fellow human beings and treated them as such. The historical record, though, shows the behavior of most Friends to have been more influenced by the world in which they lived than we would like to believe.

Gabrielle Savory Bailey writes about how the unnerving nature of her several heart attacks has been made worse by our medical establishment’s unequal attention to women, so that the kind of heart attack she has experienced is often unrecognized in hospital emergency rooms.

Jorge Luis Peña considers how the introduction of the American dollar into the formerly closed Cuban economy has led to some persons becoming “more equal” than others.

And in his bible study on Galatians 3:21–29, Kelly Kellum considers the basis in Christ for the radical spiritual equality that Friends proclaim.