There is no doubt that a great deal of what passes for Quakerism today is highly discouraging. There are a few bright spots, but the general picture is far from satisfactory. The two alternatives for which we have been willing to settle are both bad, and there is no real hope except as we are willing to face the situation with candor. It is a time for plain speech.

One of our major alternatives is a pattern of dull and undistinguished Protestantism. When the pastoral system began to come in, eighty years ago, it seemed to many Friends, especially those of the generation of my father and mother, that new life was emerging and sometimes it was. But the sad truth is that, with the growth of years, the brave little fellowships of the frontier have become standardized churches, with a hard conformity of their own making. They lack the beauty of a sacramental system; they have erected undistinguished buildings; they have a poorly trained leadership; they have little real impact upon their local communities. All that we have left, in many neighborhoods, is a little congregation, dutifully droning through three gospel songs, listening patiently to a sermon and a benediction. This is not Quakerism; it is simply Protestantism at the end of the line.

The other alternative which seemed to hold promise of newness a generation ago is likewise essentially moribund. When we established the Friends Fellowship Council it looked as though genuine hope lay in establishing new Quaker fellowships without pastors and usually in university towns. A few of these have flourished, but most have not. For the most part they tend to be militantly sectarian, under the strange delusion that they are Quakerly because they say “First Day School” instead of “Sunday School.” Most of them have little effect on their communities and seem to the public, if they are noticed at all, to be pathetic little sects meeting in the Y.W.C.A. or some other rented quarters.

Our only hope lies in new life, but the new life must come in a way radically different from anything which has been involved in the two efforts at newness inaugurated during the last century. What we need is a start as genuinely new as that which Fox envisioned in the glorious summer of 1652. Fortunately, we can see some of the elements of a form of Quaker witness which is already working. Rufus Jones was pointing the way when he did not really care whether he was invited to the ministers’ gallery at Arch Street, but did care mightily whether he had a chance to penetrate the world outside the Quaker fold.

What we need, if Quakerism is to be worth saving, is a conscious fellowship of penetration which seeks to reach both the ecclesiastical and secular society around us. Quakerism always withers when it turns in upon itself. It flowers whenever it turns outward to help establish the Anti-Slavery Movement, the Adult School Movement, the drive to humanize the prisons and the effort to lift the underprivileged races.

What we require is a new kind of base, which is neither indiscriminate nor sectarian, but a base from which we operate rather than a base in which we operate. The world is the field and that is where Quakers always belong. I am ready to begin and I welcome correspondence from others who are ready. We must help each other to gain such a discipline of mind that we can make a difference in that world, to the penetration of which we are called.

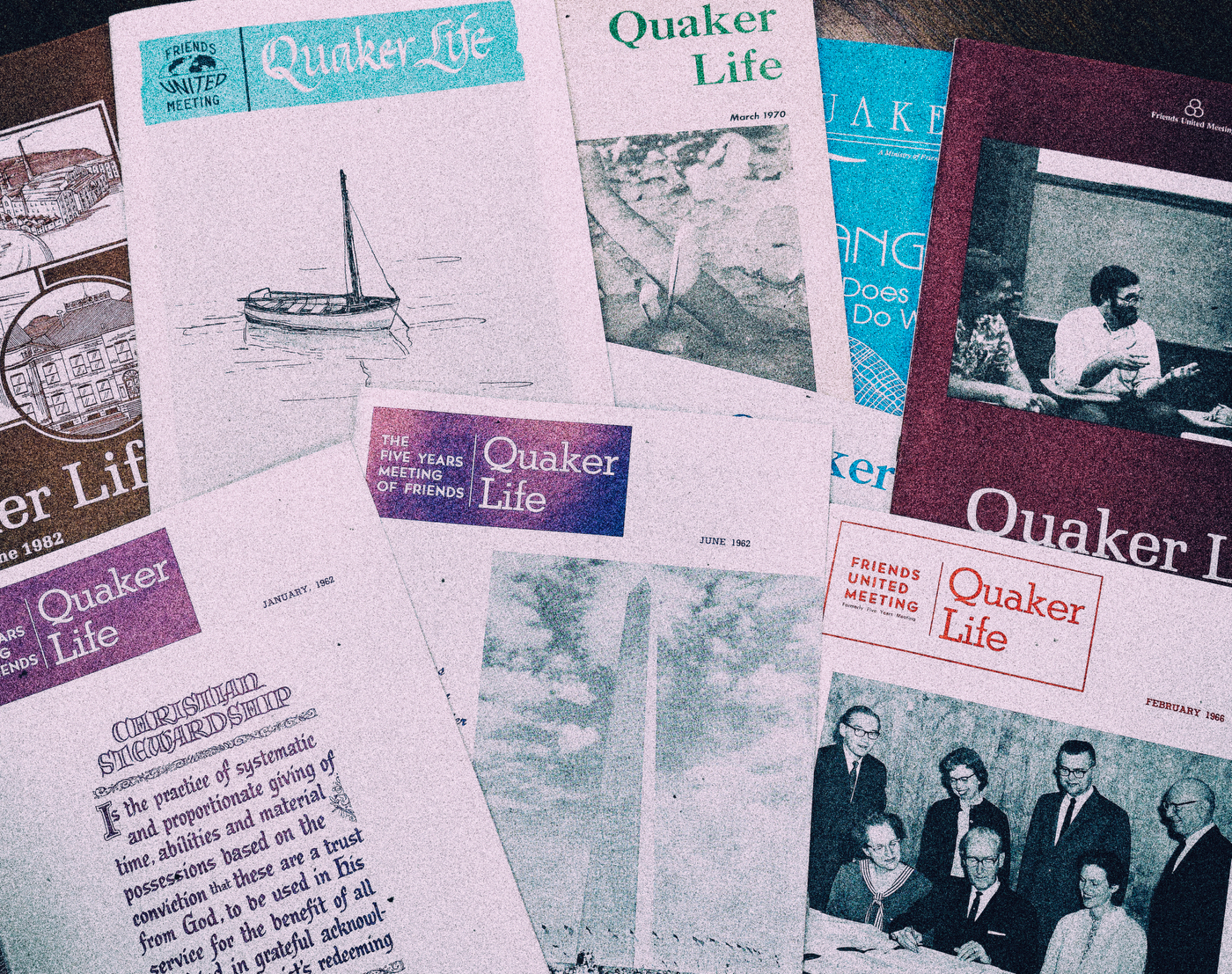

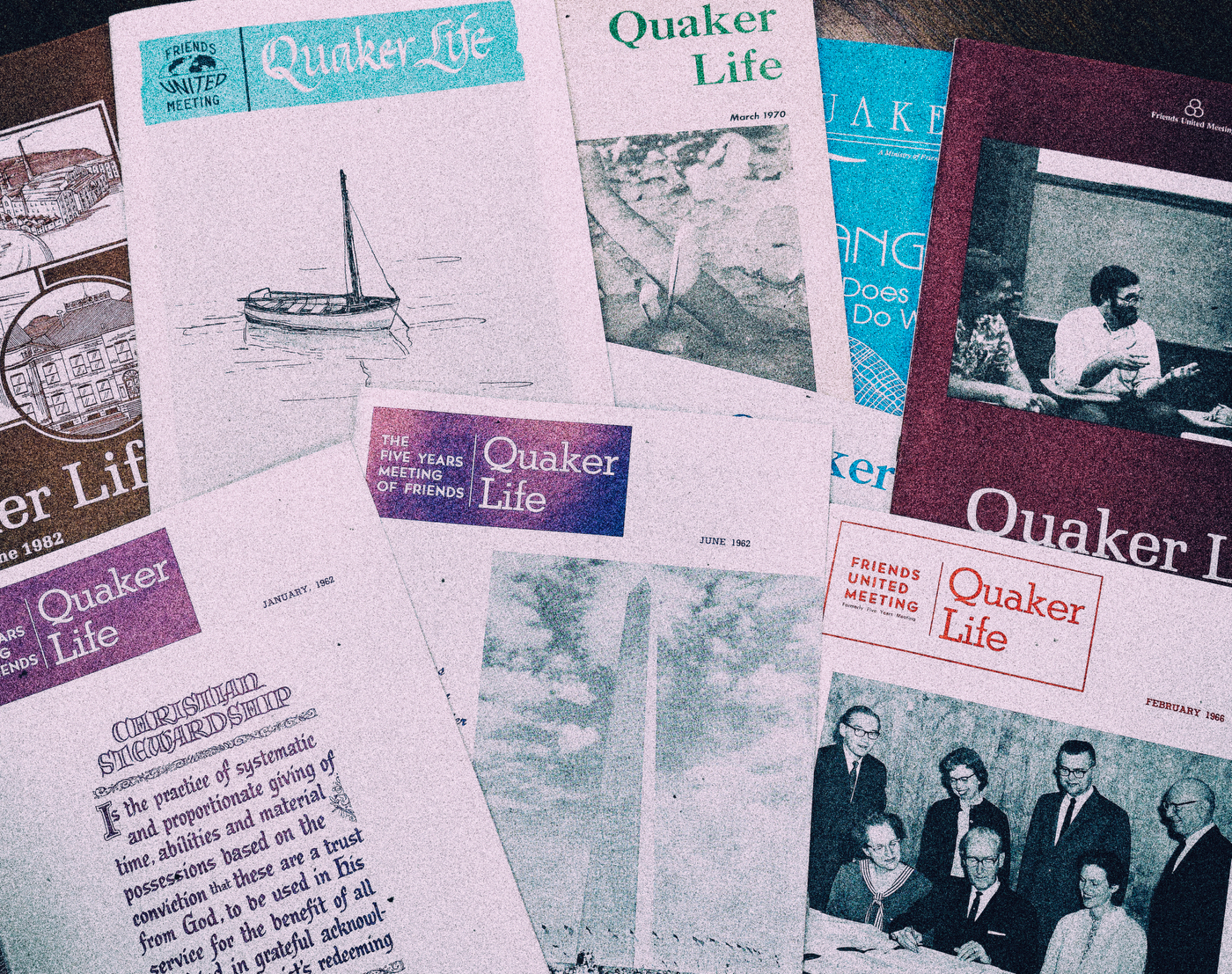

A Quaker Forward Movement (1962), D. Elton Trueblood

‘Proud of the Name Christian’ (1962), Samuel R. Levering

Building Lives That Matter (1966), T. Eugene Coffin

Drum Beats For God (1970), David Castle

The Art of Growing (1973), Howard Alexander

Can the virtues of the fathers be visited upon their children? (1970), Tom Mullen

Becoming the Friends of God (1982), Richard Foster, Howard Macy, Patrise McDaniel

Someone To Listen (1973), Mervin D. Kilmer

Thoughts on Northern Ireland (1975), Mike and Margaret Yarrow

Friends and Business (1982), Jack Kirk

Seeking Law for the Seas (1975), Miriam Levering

Faith Over Fear (1986), J. Stanley Banker

In Retreat (1986), Linda Kusse-Wolfe

“There is no doubt that a great deal of what passes for Quakerism today is highly discouraging. There are a few bright spots, but the general picture is far from satisfactory. The two alternatives for which we have been willing to settle are both bad, and there is no real hope except as we are willing to face the situation with candor. It is a time for plain speech.”

— D. Elton Trueblood, January 1962

At first look, the connecting thread between the articles in this edition of Quaker Life are not readily apparent.

Nor is there any reason to think they would be. They were chosen very much at random. The Richmond staff of Friends United Meeting sat around our conference room table and each chose one or two articles published in the Quaker Life that came out in the month and year of our birth, or closest to it. (So the articles were all written between 1962 and 1986.) There was no criteria for what we chose — just something that caught our interest.

But at a second look, there are some ideas that recur from issue to issue, or from recent issues of Quaker Life to these past issues. Of course, the deepest and most frequently recurring theme is Quaker life itself — that is, the efforts of Friends to live according to the Quaker understanding of the gospel, and to look at the world with that Quaker understanding of the gospel as a lens.

One of the most striking similarities is the attention given to the idea that Quakerism must either change and grow, or die. The emphasis on the need for change ranges from D. Elton Trueblood’s assertion that Friends only thrive when they direct their energy beyond themselves, to Eugene Coffin’s, David Castle’s, and Tom Mullen’s reflections on how to form Friends and Christians: children, women, and men who will be involved in life at God’s calling and on God’s behalf, and in that way, will find themselves living lives of purpose and meaning.

Another common theme is the exploration of practices that may lead to a deeper life with God. In 1966, Eugene Coffin writes about spiritual commitments that create disciples. In 1982, Richard Foster and Howard Macy are involved in a conversation about the books and practices that have affected their spiritual lives over the past year. In 1986, Linda Kusse-Wolfe writes about the value of retreat in allowing us to draw near enough to God that we are able to discern where we are called to serve in the world.

One interesting difference between Quaker Life past and Quaker Life present is the attention paid to psychology and counseling. Tom Mullen refers to what “experts” tell us about child-rearing. Mervin Kilmer makes the argument that many people could benefit from counseling — whether or not their pastor is able to provide it. And Howard Alexander speaks of personal growth in terms that we will likely associate with psychology. In these pieces I find an unspoken tension between whether the church or behavioral science has more to offer as we try to become the authentic persons Christ calls us to become. I may be wrong, but I believe that fifty years after these pieces were written, Friends have largely accepted that psychology doesn’t replace discipleship in forming human beings, but can help move human beings along their journey of discipleship.

In addition to the inward expression of Quaker spirituality, Friends also paid attention to its outward expression, to how one lives as a Friend in the world. Samuel Levering wrote about discovering, at the Third Assembly of the World Council of Churches, a depth of Christianity that he agreed with, but felt that he himself had not yet achieved. Jack Kirk considered the way that Friends’ faith has affected the way Friends conduct business. Stan Banker asserted that against the fear overtaking the world, faith will lead us to courage, a courage that can spread to those who are witness to it, and who can therefore come to believe, as Friends do, that God created a good world.

There are, in this collection, two very specific examples of Friends’ engagement with the world. In 1975, Mike and Margaret Yarrow wrote about the year they spent in Belfast, Northern Ireland, as Quaker representatives from the Friends Service Council, “trying to enter wholeheartedly into the feelings and thinking of all parties” to the conflict in Northern Ireland. Though they recognize unequivocally the complexity and history of the issues that divide the people of Northern Ireland, they write of their hope that community organizations at the grassroots level will be able to bring about understanding between people, and consequently peace. They are hopeful about the role that Quaker organizers might play in creating peace. They might have been surprised that it took another twenty-five years to achieve the Good Friday agreement of 1998 — or maybe not. Fifty years later, Friends are still engaged in witness and peace conversations across ethnic, religious, political, and economic lines.

Finally, I learned a great deal from Miriam Levering’s article on her participation in the Third United Nations Conference on the Law of the Sea, at the session held in Venezuela in 1975. At the time, she was cautiously hopeful that the Law of the Sea treaty might still be signed in 1975. In fact, the Conference on the Law of the Sea lasted until 1982—with the continuing participation of both Miriam and Samuel Levering—while the treaty itself (which the United States has never ratified) did not take effect until 1994, one year after it was ratified by Guyana, the sixtieth nation to sign on. Sub-agreements, chiefly concerned with protecting the marine environment and marine bio-diversity, are still being written, and seeking ratification. The work of advocating for equity above and beneath the oceans is being carried on by the Quaker United Nations Office.